Closing the Nature Funding Gap: A Finance Plan for the Planet

We need 700 billion dollars to reverse the global biodiversity crisis—here’s how we get it

In partnership with

I. The Lay of the Land and Sea

Biodiversity—the sheer number and variety of plant and animal species on the planet—is essential for the health of our planet. It is essentially nature, by another name.

In diversity there is resilience: the greater the variety of species on Earth, the better our planet can mitigate and adapt to challenges like climate change, population growth and resource depletion, and to continue providing a suitable home for all the species that live here—not least humans.

And yet biodiversity is in a sharp, long-term decline, driven largely by human behavior. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) recently warned that we are exploiting nature far more rapidly than it can renew itself. If we don’t change course, up to one million known species could disappear by 2050, with dire consequences for planetary health.

Download

If ever there was a chance to the reverse this trend, it is now. Representatives from 196 countries party to the Convention on Biological Diversity are working over the next year to negotiate a new global framework to protect nature and reverse this decades-long decline in biodiversity. The negotiators are discussing new and larger protected areas, better governance of natural resources and the sectors that utilize them, better enforcement of existing rules and regulations—and, perhaps most daunting, how we pay for all of this.

As the world grapples with both the health and financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s easy to say we can’t afford to worry about nature right now. But the cost of doing nothing—in both economic and planetary health terms—is far greater. In fact, research from the World Economic Forum shows that around half gross world product is highly or moderately dependent on nature.

We cannot have healthy, prosperous societies if we don’t protect the natural systems on which they depend. To achieve this in the long-term, we need a transformational shift in how we value nature in our economies. However, this won’t happen overnight—in the meantime, we must scale up how much we spend on protecting nature to slow and halt biodiversity loss.

II. Closing the Gap

In order to sufficiently fund the protection of nature, we need to know exactly how much we’re currently spending—and how much more is needed. In essence, we need to determine what our nature funding gap looks like. The Nature Conservancy, the Paulson Institute and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability took a deep look at these numbers as part of our new report, “Financing Nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity Financing Gap”.

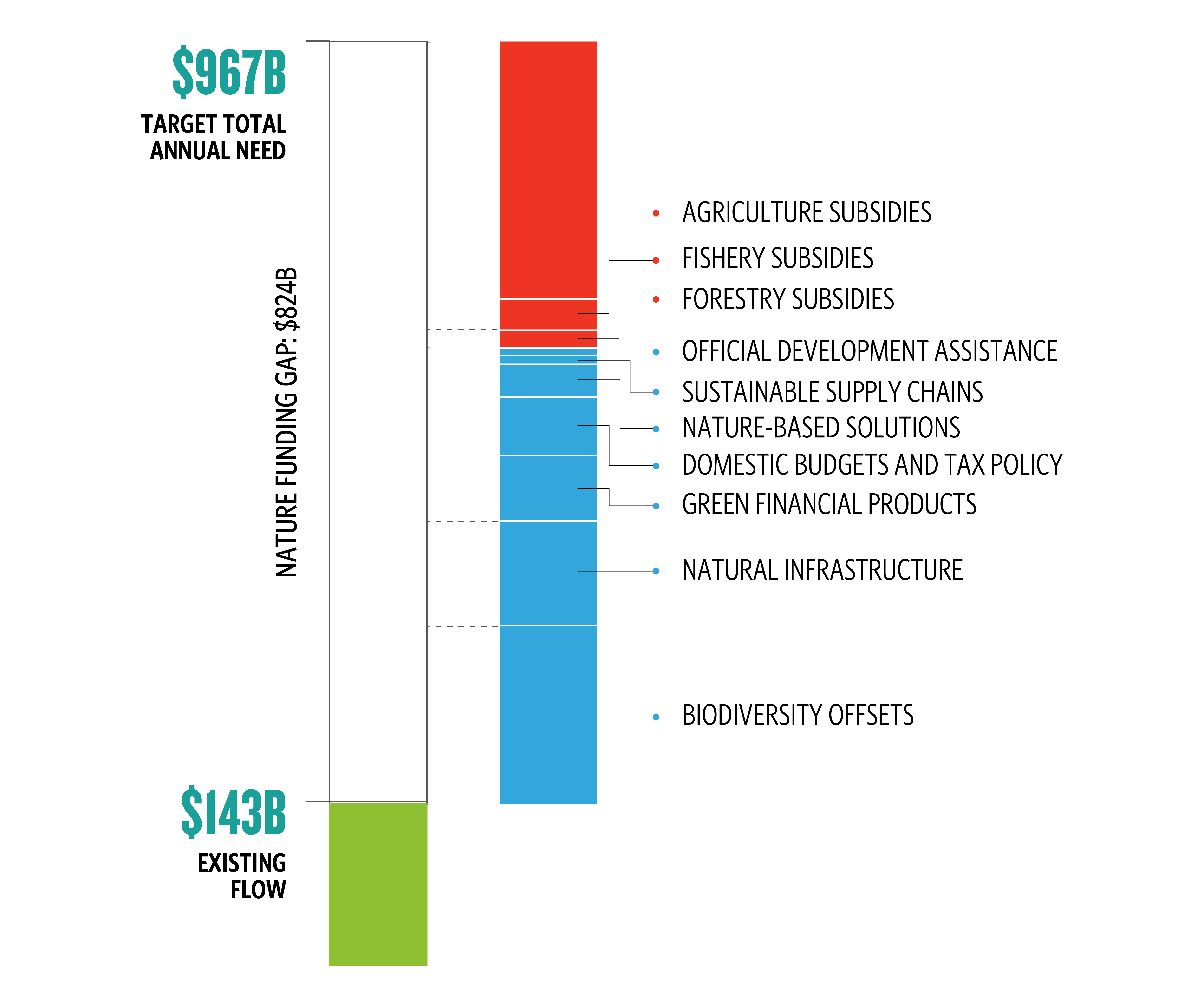

We estimate that in 2019, the world spent between US$124 and US$143 billion per year on activities that benefit nature worldwide. This represents a near-tripling in funding since 2012—but it’s still not nearly enough. Annual government spending on agricultural, forestry and fisheries subsidies that degrade nature is up to four times higher than spending that benefits nature.

To reverse the decline in biodiversity by 2030, we need to be spending US$722-967 billion per year. That puts the nature funding gap as high as US$824 billion per year.

This is substantially higher than previous estimates. Why? Ours is the first analysis to include the cost of shifting agriculture, infrastructure and other high-impact sectors to more sustainable business models. Without making substantial changes to the sectors that are driving the degradation of nature, we won’t halt biodiversity loss, no matter how significant our actions are in other areas.

This is substantially higher than previous estimates. Why? Ours is the first analysis to include the cost of shifting agriculture, infrastructure and other high-impact sectors to more sustainable business models. Without making substantial changes to the sectors that are driving the degradation of nature, we won’t halt biodiversity loss, no matter how significant our actions are in other areas.

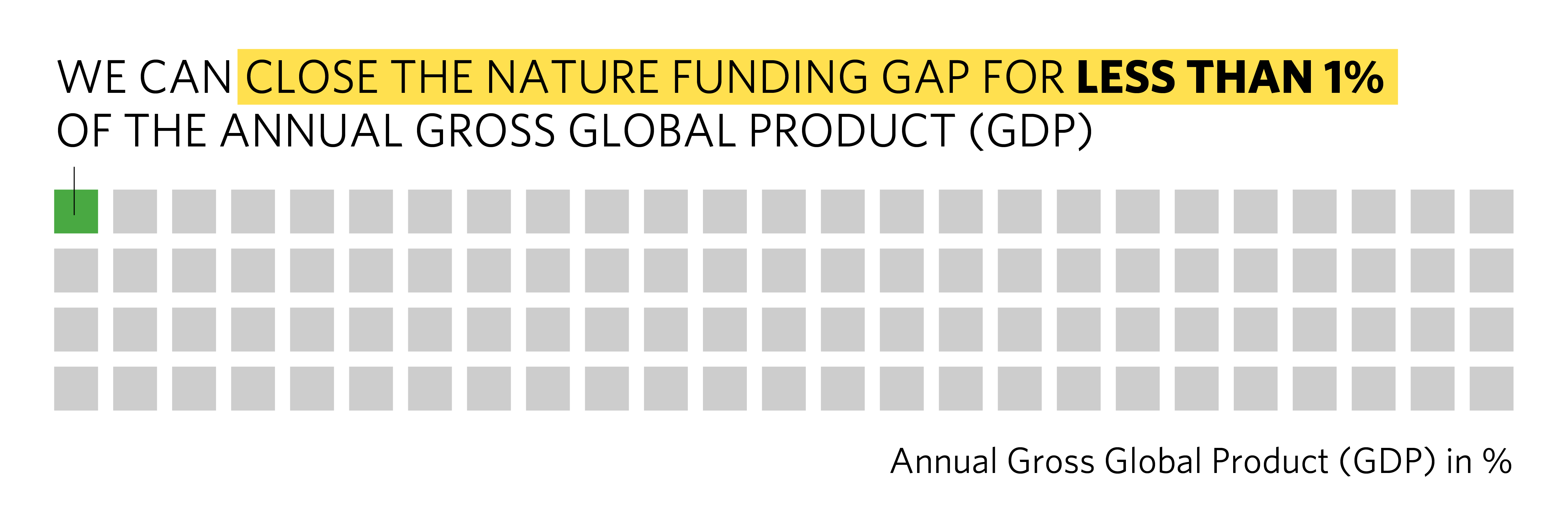

But as large our funding gap might be, there is some hopeful news: we can close the gap for less than one percent of annual gross global product. For comparison, that’s roughly equivalent to the annual GDP of Poland, or that of the state of North Carolina. We could close the nature funding gap with what world spends on cigarettes in a year, or soft drinks. It’s practically a rounding error considered next to the trillions of dollars world governments are currently injecting into their economies through stimulus programs, or the tens of trillions in private assets around the world.

Presented here are a range of mechanisms that, if implemented at the right scale and combined with philantropic spending, could unlock the funding we need. These solutions come from all across society. Some are new financial instruments for leveraging private investment, while others are policy-related changes. Many are governmental, but others call on private corporations to rethink their supply chains and investments. All call upon individuals to do more, whether they are leaders in government, business or finance, or just everyday people with an interest in a healthy planet.

Quote

We can close the nature funding gap for the cost of what the world spends on cigarettes or soft drinks

III. Reduce, Produce, Invest

If we think of the nature funding gap as a monolithic number—approximately 700 billion dollars per year—it sounds daunting. But when we split that amount into a series of smaller, more-manageable categories, closing the gap begins to appear doable.

In fact, it’s possible we could close nearly half this gap with no new funding. Much of what we need is better deployment of existing funds and smarter policy and investment choices—shifting the flow of capital away from harmful behaviors and toward outcomes that benefit nature. Other recommendations work by getting more bang for the buck out of what we already spend.

Estimate of Growth in Financing Resulting from Scaling Up Proposed Mechanisms by 2030

We have grouped our recommended approaches into three categories: those that reduce harm, those that generate new revenue and those that generate increased benefits by making different use of existing funds.

1. Reduce Harmful Economic Activity (up to US$293 billion*)

Reducing economic activity that harms nature in turn reduces the need for funding to counteract these impacts. Changes in the way various sectors operate—and the operations that governments subsidise—can go a long way toward closing the nature funding gap. This will require us to improve and scale up risk management practices in the financial sector and reduce and redirect harmful subsidies, which will reduce the need for spending on biodiversity, and to reform supply chains to create more positive revenues for nature. *It’s worth noting that while our analysis doesn’t calculate a specific financial value for investment risk management at this time, it’s unlikely we’ll close the funding gap by 2030 without reform in this area too.

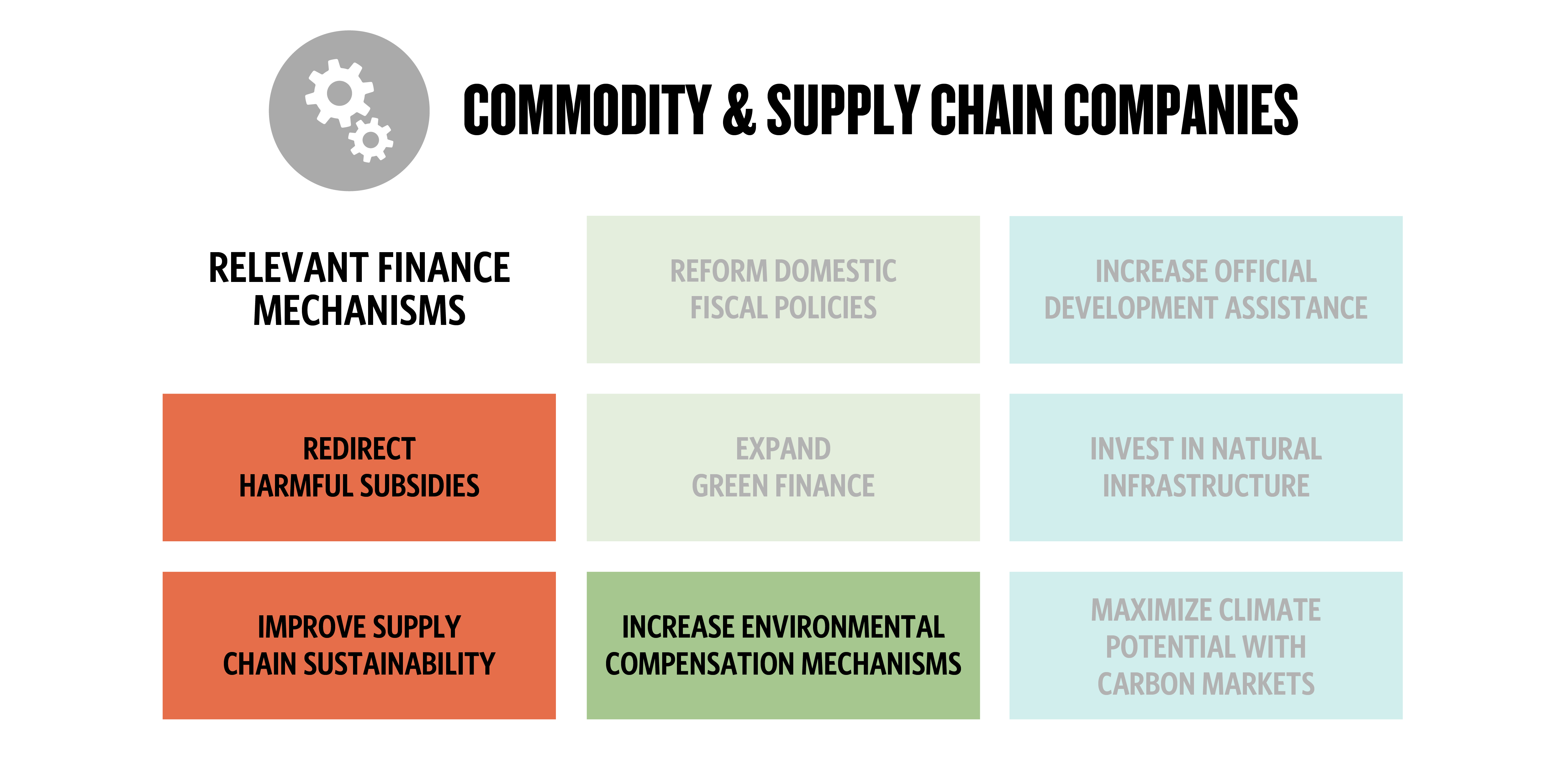

- Redirect Harmful Subsidies: Subsidy reform represents the single biggest opportunity to close the funding gap. As much as US$542 billion per year is currently spent on agricultural, fisheries and forestry subsidies that are harmful for nature. Redirecting those payments to incentivise more sustainable practices would benefit nature while also mitigating climate change and improving food security.

- Improve Supply Chain Sustainability: The historical impact of global supply chains on nature has been largely negative, characterised by unsustainable practices in agriculture and other industries. However, a shift towards more responsible supply chain management practices offers an opportunity to avoid harm and even positively impact nature.

2. Produce New Revenue ($169-416BN)

Even if we greatly reduce harmful economic activity, we still need new sources of funding. The key is to generate revenue in smart, fair and equitable ways that promote the needs of nature while sharing the financial burdens among those who either profit most from biodiversity or can better afford it. Revenue generating mechanisms include:

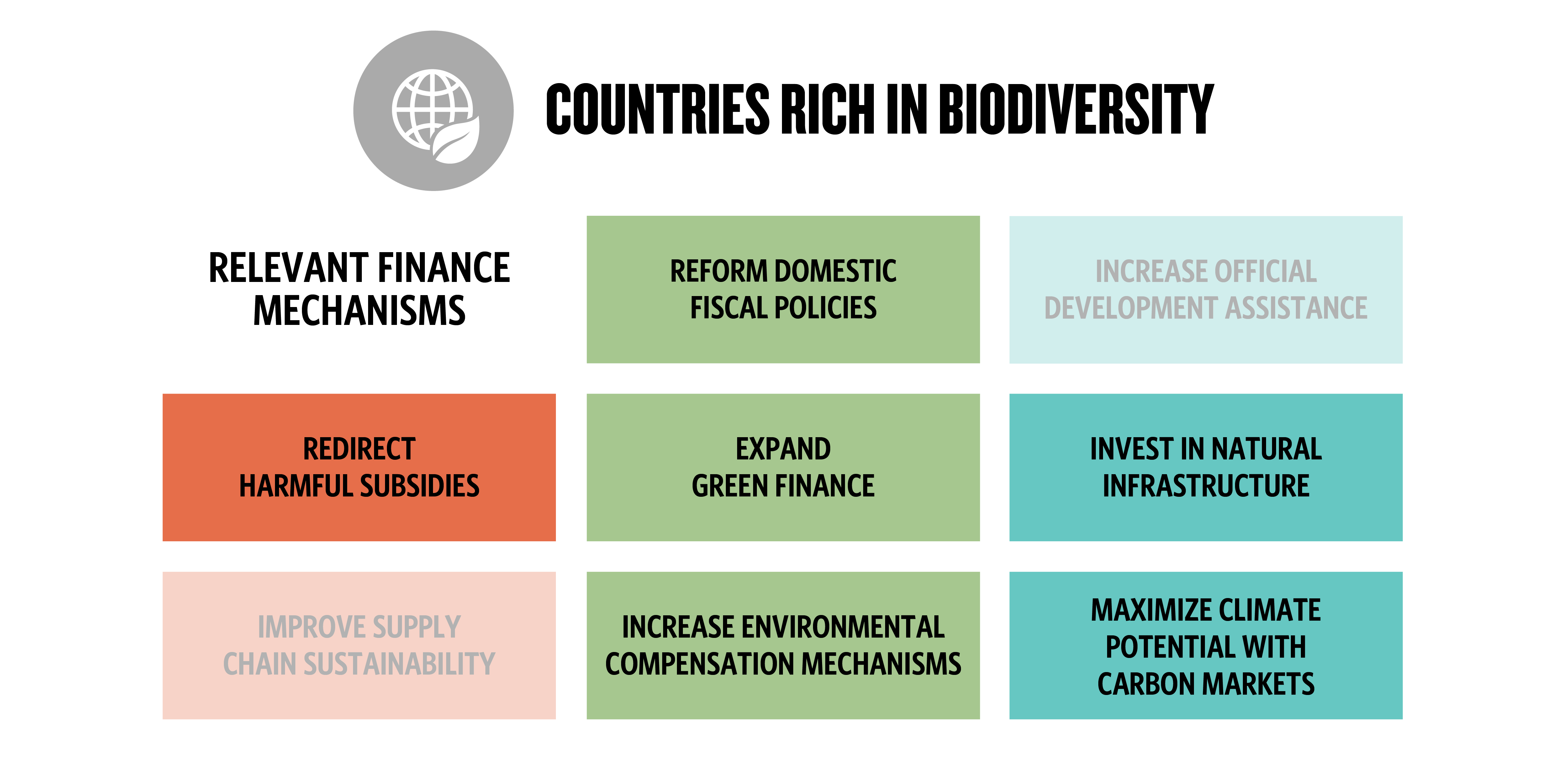

- Reform Domestic Fiscal Policies: Governments have significant power to influence and direct the economy in ways that both increase revenue and discourage activities that harm nature, including new funding streams through taxes, fees, debt relief, loans and tariffs.

- Expand Green Finance: Interest in sustainable investing has exploded in recent years, but investments that directly benefit nature have lagged behind investments in low-carbon infrastructure. Financial institutions can help by expanding investment opportunities in green bonds, low-interest green loans and environmental-impact bonds. Governments can assist by creating clear guidance and standards for these investments.

- Increase Environmental Compensation Mechanisms: Agriculture, infrastructure and extractive industries that have negative impacts on nature should compensate and offset the harm they cause by restoring degraded ecosystems or protecting at-risk ecosystems. Put another way, “you break it, you pay for it.”

3. Invest More Wisely ($138-198BN)

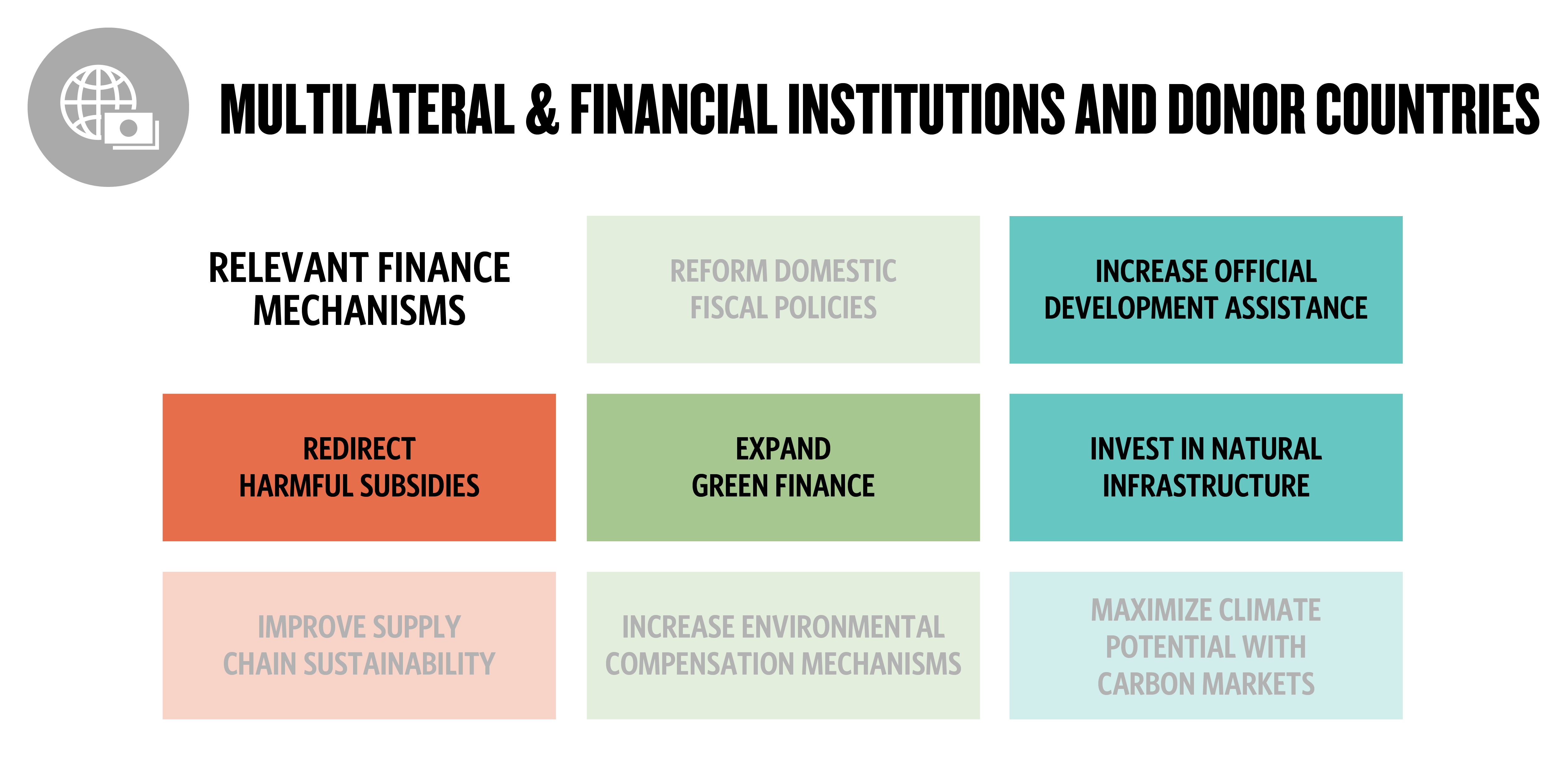

In addition to reducing harm and generating new revenues, there’s the question of how we use existing public and private investments. Institutions are already investing trillions of dollars on infrastructure, climate mitigation and development assistance; with smart changes in policy, we can redirect far more of these payments toward investments that pay dividends for nature, too. Examples include:

- Increase Official Development Assistance for Biodiversity: Expanded aid to biodiversity-rich recipient nations from multilateral institutions and donor nations can take the form of debt forgiveness, direct grants and technical assistance in support of biodiversity initiatives.

- Invest in Natural Infrastructure: Reefs, forests, wetlands and other natural systems provide habitat for wildlife while also delivering important services like water management and coastal protection. In some cases this natural infrastructure may be more cost-effective than engineered solutions.

- Maximise Nature's Climate Potential: Protecting and restoring natural lands is one of the best ways to mitigate carbon emissions—by investing in these natural climate solutions, governments can meet their climate goals and protect nature. Including natural landscapes into carbon markets or leveraging other financial incentives creates additional economic rationale to protect nature.

Key Mechanisms for Closing the Global Nature Funding Gap by 2030 (in $B/yr)

Quote

It’s possible we could close nearly half the nature funding gap with no new funding.

IV. Putting Funding into Action

Every nation, every sector and every citizen of the world has a role to play in protecting nature. The decline and degradation of the natural world is a global problem and will require a global response that is equitable, in terms of the sacrifices demanded from participants as well as the benefits it confers to them. Securing participation from all groups—and cooperation amongst them—will be key to closing the gap.

Changes in government incentives—including the reform or redirection of subsidies—will be key to driving these changes. Companies can have a major impact by reducing consumption, offsetting extractive activities with commensurate biodiversity-preserving behaviors, and implementing programs that improve efficiency and sustainability throughout the global supply chain.

All countries must fully acknowledge and value the role biodiversity plays not just in healthy ecosystems, but in healthy economies. Nature should be seen as a finite resource to be valued and its use sustainably managed. Equipped with a more complete understanding of the benefits of biodiversity—not least climate change mitigation and adaptation—leaders at the highest levels of government should mainstream biodiversity in their policy, legal and fiscal decision-making.

Meanwhile, multilateral institutions and donor countries must develop programs of bilateral and multilateral Official Development Aid to support less-developed nations who demonstrate clear and sustainable programs that halt biodiversity loss. Banks and financial institutions can also incentivise biodiversity-enhancing efforts through green lending priorities and policies.

And, ultimately citizen-consumers play a key role in protecting biodiversity: first by understanding the scope of the problem and the solutions at hand; and second, by choosing to support and work for companies and lending institutions that are similarly committed to long-term sustainability goals and initiatives and, in democracies, voting for politicians who prioritise nature protection.

And, ultimately citizen-consumers play a key role in protecting biodiversity: first by understanding the scope of the problem and the solutions at hand; and second, by choosing to support and work for companies and lending institutions that are similarly committed to long-term sustainability goals and initiatives and, in democracies, voting for politicians who prioritise nature protection.

Quote

Closing the gap is not just about finding the money. It’s a matter of priority: what do we value most in the world?

V. The Road Forward

The natural world has always provided vital resources and inspiration to human societies. Somewhere, however, the balance tipped and nature became the object of exploitation. Today, not only are our lands and waters polluted and depleted, but the number and variety of plants and animals—the diversity of living things on Earth—is in serious decline. The intertwined biodiversity and climate crises threaten life on our planet as we know it.

We need to reinvest in our planet, but closing the nature funding gap is not just a matter of finding the money. It’s a matter of priority: what do we value most in the world? As our research shows, much of the funding we need to protect nature originates in the private sector; however, governments must set the conditions and incentives for that funding to flow in ways that generate nature-positive outcomes. In many ways our funding problem is a policy and regulatory problem.

The 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity is now scheduled to take place in Kunming, China, in 2021. As countries hash out the term of a “new deal for nature,” there has never been a better time for world governments to address these issues. Every solution outlined here will not work in every country, but leaders can identify those that are most appropriate for their countries and their economies to develop a plan that funds their commitments to nature. And collectively, we can create a finance plan for the planet.

When we succeed, the payoff will come in the form of natural resilience that benefits us all: greater food, water and economic security; a more stable climate; reduced risk of pandemics; and, not least of all, the intangible benefits nature brings to us every day. It is a small price to pay.

Download

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.