Australia’s Endangered Animals

10 Australian endangered animals at risk of extinction

Time is running out for threatened species

Help save our unique & endangered wildlife and their homes before they disappear forever!

DONATE NOW >In Australia we have a remarkable landscape. It’s populated by plants and animals unlike anything found anywhere else in the world. It’s a legacy that defines and distinguishes Australia. But it’s a legacy at risk of further loss.

As of March 2021, the Australian Government listed an extra 13 species as extinct1 under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

That brings the total number to 100 of Australia’s endemic species declared as extinct (or extinct in the wild) since the colonisation of Australia by Europeans in 1788. The actual number of extinctions is likely to be far more than those recognised in formal lists2.

These extinctions have occurred since European settlement. Sadly, Australia has the highest mammal extinction rate in the world.

Only 60 years ago, we could still find quolls around Melbourne. Pig-footed Bandicoots, Crescent Nailtail Wallabies and Desert Rat-kangaroos in Australia. Those animals have gone.

Species that had thrived on the Australian landscape for hundreds of thousands, even millions of years have tragically disappeared in just a few decades. This is mostly due to predation by, or competition with, feral animals and habitat destruction.

Quote

If we don’t manage and protect our threatened species, then EXTINCTION is the end result.

Get to know 10 endangered native Australian species at risk of disappearing forever

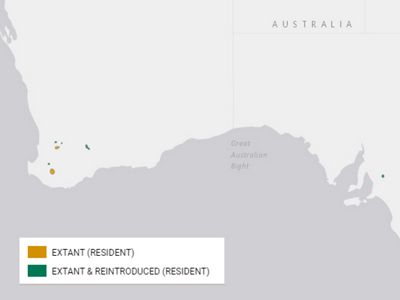

1. Numbat

EPBC Status: Endangered

Scientific name: Myrmecobius fasciatus

The Numbat is small to medium sized marsupial that’s the faunal emblem of Western Australia. They survive in two naturally occurring populations in the south-west of Western Australia. Other reintroduced populations exist in protected reserves in New South Wales and South Australia.

Their termite-only diet means they need to be active during the day to find food.

Due to their size, Numbats are hunted by many animals like feral cats, feral foxes, dingoes and birds of prey.

They spend nights hiding in hollow logs or burrows that are too narrow for predators to enter. To further protect themselves from predators at night, Numbats use their very thick-skinned rump to block the entrance. Now that’s using your behind to get ahead.

2. Gouldian Finch

EPBC Status: Endangered

Scientific name: Erythrura gouldiae

The Gouldian Finch is perhaps the most beautiful small bird in the world. Sadly, beauty is one of the reasons this rare bird is endangered today.

The impressive colour of its feathers appealed to bird enthusiasts around the world. A large number of them were trapped in the wild for the local and international bird trade up until the early 1980s. But, the main causes of their decline are changes in habitat as a result of land clearing and fire.

Fire plays a large role in their survival. In the dry season, they rely on controlled fires to burn the undergrowth, so they can find seeds on the ground to feed on. In the wet season, they like to live in areas which have been burned in the previous dry season. This produces lush new growth with plenty of seeds for food.

Improved burning practices are helping them make a comeback. We’re supporting Indigenous land managers across northern Australia such as Fish River Station. They’re working hard to improve their fire practices to protect the habitat of this stunning beauty.

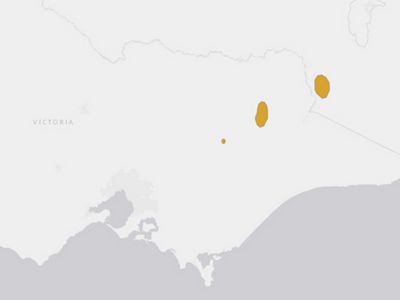

3. Mountain Pygmy-possum

EPBC Status: Endangered

Scientific name: Burramys parvus

As temperatures become warmer, animals that depend on cooler habitats may be more vulnerable to climate change. One example is the Mountain Pygmy-possum. These tiny possums, not much bigger than mice, are only found in alpine and sub-alpine regions of southern Victoria, and around Mt Kosciuszko in New South Wales.

Each year they go through a prolonged hibernation over winter of up to seven months. They curl up in their nest that’s two to four metres under the snow and wake occasionally to nibble on their stored food. They only emerge in early spring to mate. Mountain Pygmy-possums spend most of their time amongst alpine and sub-alpine boulderfields and rocky screes.

Unlike most other possum species, they’re usually found close to the ground, where they hunt for their main food sources; Bogong Moths and other invertebrates. They also eat seeds and berries.

There are around 2,000 Mountain Pygmy-possums in the wild. Their habitat needs limit their distribution. This affects their ability to significantly increase their population. Consequently, genetic loss is a key threat to the small populations and the protection of habitat is critical.[1]

4. Regent Honeyeater

EPBC Status: Critically Endangered

Scientific name: Anthochaera phrygia

The Regent Honeyeater, with its brilliant flashes of yellow embroidery, was once seen overhead in flocks of hundreds. Widespread clearance of their woodland habitat and competition for nectar from larger, more aggressive honeyeaters has caused their numbers and range to decline dramatically in the last 30 years.

The Regent Honeyeater although a striking and distinctive bird, was once known as the ‘Warty-faced Honeyeater’. This was due to the warty bare skin around the eye.

As the name suggests, Regent Honeyeaters feed mainly on nectar from a small number of eucalypt species. These birds act as a pollinator for many flowering plants. They also feed on other plant sugars, as well as on insects, spiders and fruits.

They can be found in eucalypt forests and woodlands, particularly in blossoming trees and mistletoe. They can also occasionally be spotted in orchards and urban gardens.

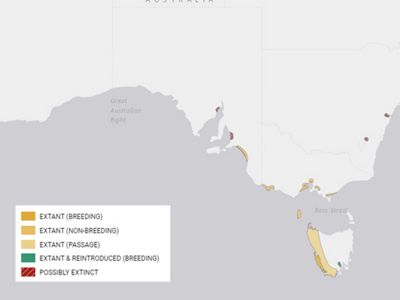

5. Orange-bellied Parrot

EPBC Status: Critically Endangered

Scientific name: Neophema chrysogaster

The Orange-bellied Parrot forages on coastal saltmarsh vegetation and adjacent weedy pastures. They can be found in areas where TNC is restoring coastal wetlands.

They are a small, migratory ground-dwelling parrot and are a treasure to behold – their palette of colours make them a living work of art. Sadly, they’re also one of our most threatened species. With only up to 50 adults in the wild, they’re at great risk of extinction.

There are only three migratory parrot species in the whole world. The Orange-bellied Parrot is one of them. From Tasmania, they migrate to coastal Victoria and South Australia to spend autumn and winter. They usually stay within 3km of the coastline to forage on coastal saltmarsh vegetation and adjacent weedy pastures. They can be found in areas where TNC is restoring coastal wetlands.

Their breeding range has declined significantly. Now, breeding is only known to occur at Melaleuca in south-west Tasmania.

The decline of the Orange-bellied Parrot is likely influenced most strongly by habitat loss and degradation in the non-breeding range. Changes to fire management practices in the breeding range may also have had an effect.

6. Eastern Quoll

EPBC Status: Endangered

Scientific name: Dasyurus hallucatus

The Eastern Quoll is a spotted carnivorous marsupial of Australia’s north. They feed primarily on invertebrates, but also eat fleshy fruit (particularly figs) and a wide range of vertebrates, including small mammals, birds, lizards, snakes and frogs.

In the wild, they live for about one to a maximum three years, with females living longer than males.

Eastern Quolls living in rocky habitats, where there are fewer feral predators, are larger than those living in savanna habitats such as the Kimberley.

Eastern Quolls are susceptible to cane toad toxins, fire and introduced predators such as foxes and cats. They’re now absent from many parts of its former range, particularly the savanna country.

The impacts of feral animals are exacerbated by extensive wildfires, habitat degradation through over-grazing and urban development. The changes in habitat reduce ground cover and hence shelter for these small mammals.

To help protect this highly adaptable species, Eastern Quolls are finding refuge on some offshore, toad-free islands. They’re also thriving on Fish River Station, Northern Territory and benefitting from better land management practices by Traditional Owners, the Nyikina Mangala people in the Kimberley. Nyikina Mangala Rangers are conducting surveys to monitor their native animal species closely to ensure that no species will be lost.

Help save the Eastern Quoll

$75 could support conservation on 150 hectares of habitat for the Eastern Quoll

DONATE NOW >

7. Woylie

EPBC Status: Endangered

Scientific name: Bettongia penicillata

The endangered Woylie or Brush-tailed Bettong is an extremely rare, rabbit-sized marsupial, only found in Australia. The name is derived from “walyu” in the Noongar language.

Bushmen also called Woylies "farting rats", inspired by the abrupt noise it makes when disturbed.

As with potoroos and other bettong species, the Woylie has a largely fungivorous diet. They dig for a wide variety of fruiting bodies. When the Woylie was widespread and abundant, they played an important role in the dispersal of fungal spores within desert ecosystems that helped native plants grow.

Like many small Australian marsupials, predation from the introduction of foxes and cats caused their rapid decline. Other factors include disease, competition with rabbits for food, changes in fire regimes and impact from grazing animals accompanies by land clearing for agriculture.

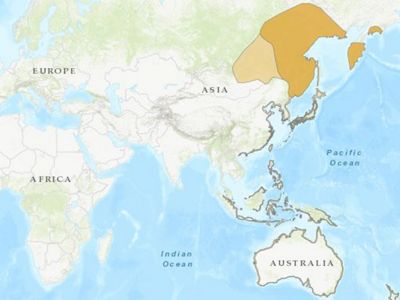

8. Eastern Curlew

EPBC Status: Critically Endangered

Scientific name: Numenius madagascariensis

The Eastern Curlew is the largest of all the world’s shorebirds. Their impressive bill is used to probe mud and dig up crabs and molluscs which is their main food source in Australia. Sadly, they’re critically endangered and have declined by more than 80% in the past 40 years.

The Eastern Curlew takes an annual migratory flight to Russia and north-eastern China to breed. They arrive in Australia to fatten up before the long journey up north again to breed.

They can be spotted in coastal regions of north-eastern and southern Australia. They can also be found at the Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary where their habitat is protected.

The Eastern Curlew is declining as a result of habitat destruction and alteration to the chain of coastal wetlands along their migratory path. The loss of even small areas of wetland can be devastating.

Many of these wetlands are being damaged by urban development, flood mitigation, agriculture and pollution. Direct disturbance on beaches by humans, domestic dogs and vehicles can cause stress to birds.

You can help the Eastern Curlew and other shorebirds with these actions:

- Control dogs on beaches and in estuaries

- Protect coastal areas from pollution

- Protect foraging and roosting areas from disturbance or inappropriate development

9. Black-flanked Rock-wallaby

EPBC Status: Endangered

Scientific name: Petrogale lateralis

The Black-flanked Rock-wallaby, or Warru in the Western Desert, was once found in abundance across parts of Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. It is now endangered.

They live in groups of 10 to 100 individuals. This small nocturnal wallaby lives in rugged rocky areas where they shelter during the day in caves, cliffs, screes and rockpiles. They emerge at dusk to feed on grasses, forbs, shrubs and occasionally seeds and fruits. They feed as close to their shelter as possible, especially where predators are present. Because most of their water comes from their diet, they rarely drink and can conserve water by taking shelter from the heat in rocky caves.

The clearing of its habitat, changes to fire patterns and introduced foxes and wild cats, all threaten their existence. They only survive today in small isolated populations. Our support of the Martu people in the Western Desert helped them make a comeback.

Help save the Black-flanked Rock-wallaby

$75 could support conservation on 300 hectares of habitat for this wallaby & other species

DONATE NOW >

10. Purple-crowned Fairy-wren

EPBC Status: Endangered

Scientific name: Malurus coronatus

The Purple-crowned Fairy-wren can be found in patches of dense river-fringing vegetation. These striking fairy-wrens occur as two subspecies. The western subspecies is found in the Kimberley region of Western Australia including the traditional Country of the Nyikina and Mangala people in the Fitzroy River, and in the Victoria River District of the Northern Territory.

Purple-crowned Fairy-wrens are co-operative breeders. Offspring from previous breeding seasons will remain with their parents and help raise subsequent broods. They spend their days flitting around between pandanus, river grasses and shrubs, and scratching in the leaf litter to find their prey of insects and sometimes seeds.

During the breeding season, adult males develop the spectacular bright purple feathers on their crown, bordered by a black face mask and capped with an oblong black spot on top of the head.

Current pastoral practices and fire regimes are detrimental to their preferred habitat and are leading to decline and disappearances of these fairy-wrens. The greatest threat to the species is degradation or loss of habitat. Livestock seeking water eat and trample riparian vegetation, and more frequent and/or more intense fires have also been detrimental in some places. Heavy weed invasion may also have adverse effects now and in the future. Low breeding success has also been largely due to nest predation by feral cats and rats.

Important projects such as cool-season burning across northern Australia is improving the chances of survival for species like the Purple-crowned Fairy-wren. It’s also supporting indigenous land managers in their efforts to build better lives for their communities.

Sources:

1 Amendments to the EPBC Act list of threatened species, Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment

2 J.C.Z.Woinarski, M.F.Braby, A.A.Burbidge, D.Coates, S.T.Garnett, R.J.Fensham, S.M.Leggea, fN.L.McKenzie, J.L.Silcock, B.P.Murphy (2019), Reading the black book: The number, timing, distribution and causes of listed extinctions in Australia, Biological Conservation 239:108261

Want to know more?

Find out how we're helping to conserve Australia's iconic natural landscapes and crucial wildlife habitats.